School on Sundays!

An Intimidating puzzle, which leads to exploring projective geometry…

I designed a toy puzzle, which seems very hard to solve but has a surprisingly simple looking geometric solution.

Puzzle

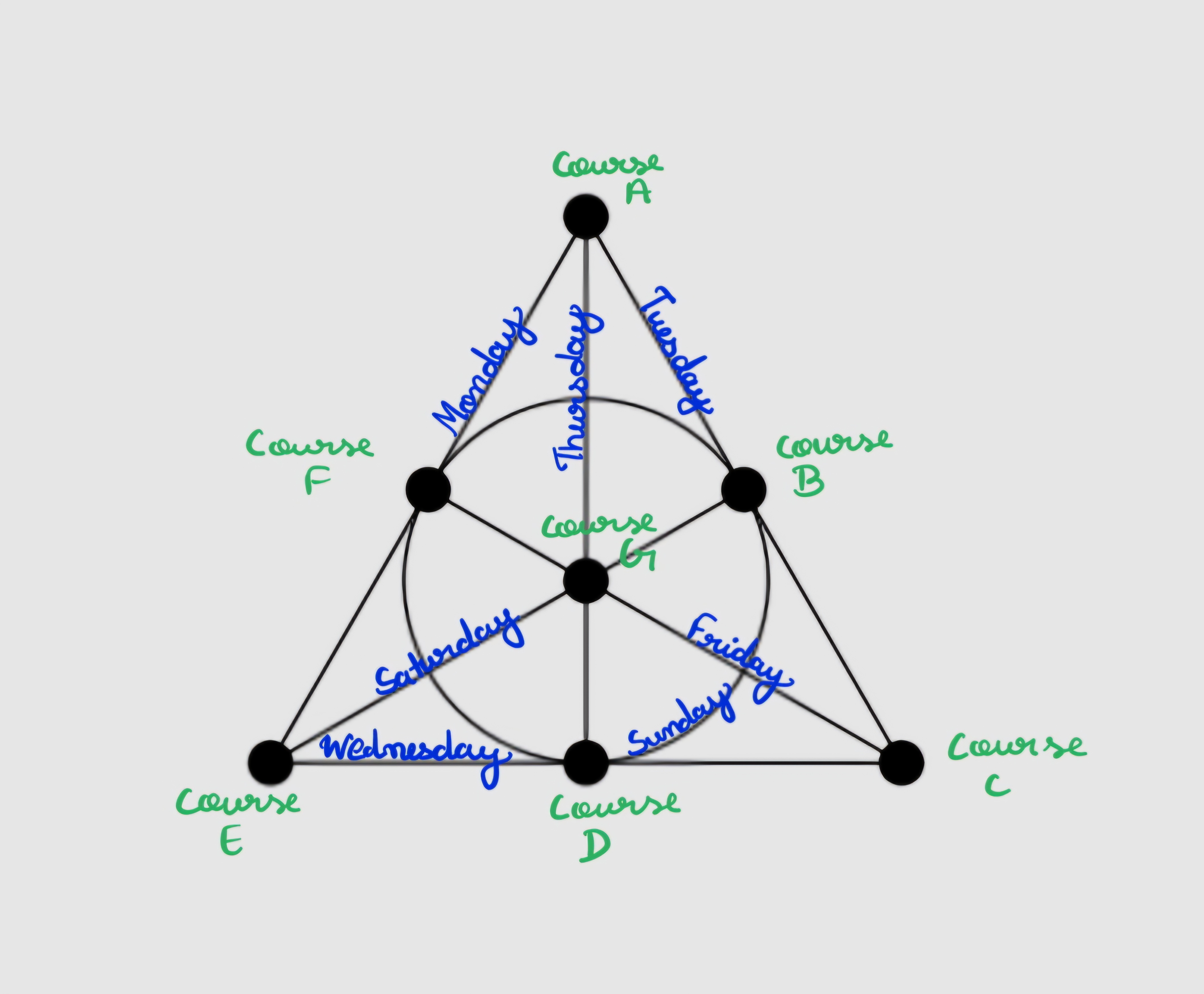

You are the head of a committee in charge of making timetables for school students. The school offers seven courses. Every day of the week (including Sundays), classes are scheduled. As the school works even on Sundays, every day is kept light with exactly three classes. You are asked to schedule classes so that, every day, three different courses are taught. Also, given two different days of the week, there is precisely one course common on both days, and given two different courses, there is exactly one day when both these courses are taught. Furthermore, there should be a set of 4 courses such that no three are taught on the same day.

It seems like a monumental task! Does such a timetable exist? If so, how to make one?

Solution

The quest for finding a solution to this puzzle takes us on a tour into the fascinating world of combinatorial design.

Combinatorial design theory is the part of combinatorial mathematics that deals with the existence, construction, and properties of systems of finite sets whose arrangements satisfy generalized concepts of balance and/or symmetry.

Specifically, into finite projective planes…

First, let’s see what a finite projective plane is,

A projective plane is a set of “points” and “lines” lines such that they follow the following properties:

- Given two distinct points, there is exactly one line passing through it

- Give two distinct lines, they intersect at exactly one point

- There exists a set of 4 points such that no three points are colinear.

I have put points and lines under quotation because these need not necessarily be the points and lines we are used to (That of $\mathbb{R}^2$). However, these can represent a more general quantity.

So, more generally, a projective plane is a non-empty set $X$ (whose elements are called “points”), along with a non-empty collection $L$ of subsets of $X$ (whose elements are called “lines”).

One example of a projective plane is an extended Euclidean plane, which is constructed from the ordinary Euclidean plane. As an exercise, try to figure out by adding what set of lines and/or points one can achieve this construction. (After thinking through, click to see how this can be done)

Ordinary Euclidian plane, one can turn into the projective plane (called the extended Euclidian plane) by the following procedure:

- Consider a maximum set of mutually parallel lines. To each of such a set, associate a single new point, which is considered incident with each line in this set. These points are called points at infinity.

- Now, we need to have a line passing through the points at infinity. So, introduce a new line, which is considered to be incident with all points at infinity and no other points. This is called the line at infinity.

There is a geometric way of constructing an extended Euclidean plane. Each point in the Euclidean plane $\mathbb{R}^2$ can be mapped to a geometric line in $\mathbb{R}^3$ which passes through the origin, and each line in $\mathbb{R}^2$ can be mapped to geometric plane through the origin in $\mathbb{R}^3$.

Now we have some flavor of projective planes. When the number of points and lines is finite, it is called a finite projective plane.

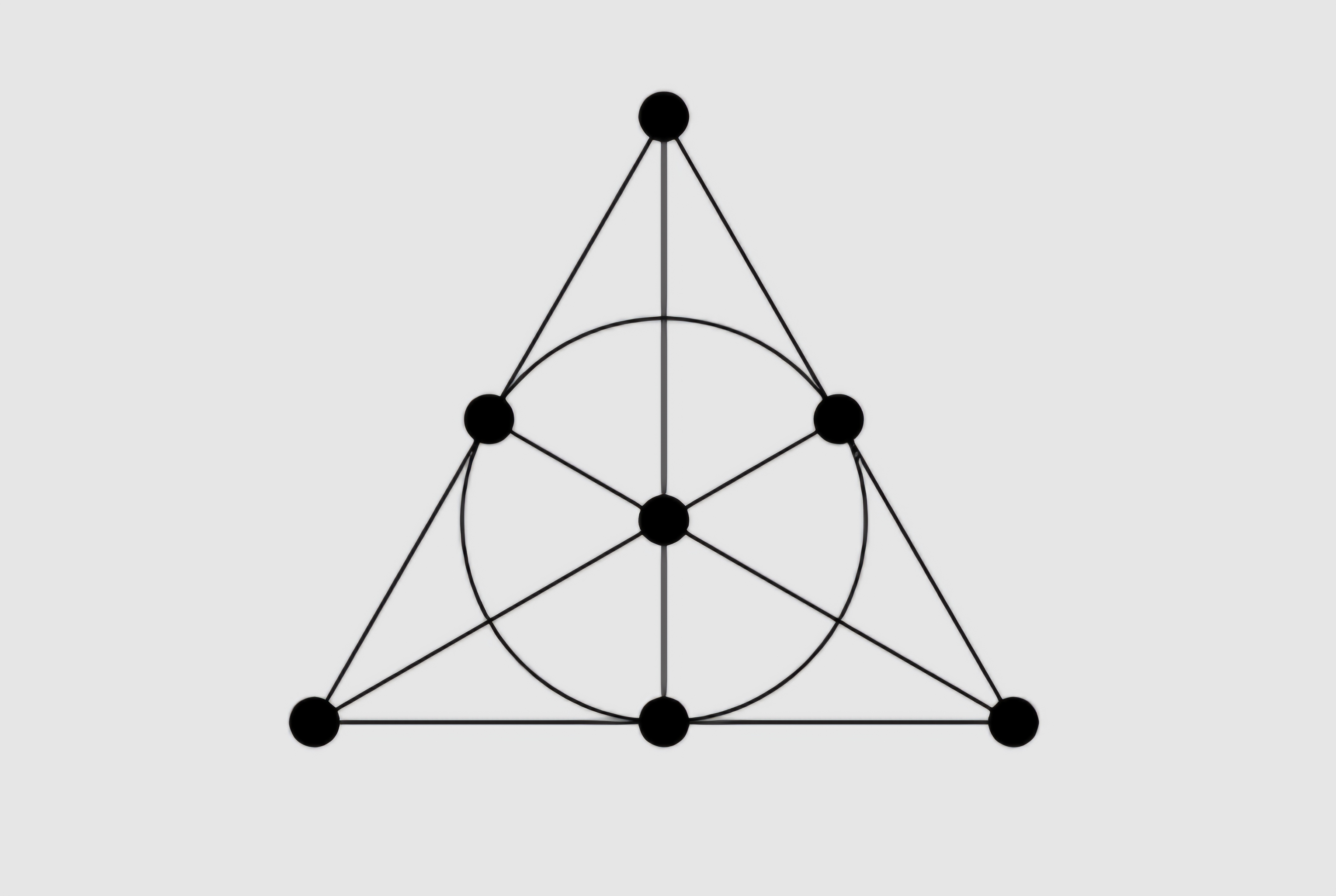

A very famous example of a finite projective plane is a Fano plane.

We can see that this satisfies all the conditions listed for the projective plane. This has a finite number of lines and points, and both are equal to 7.

Try to make a finite projective plane with 8 or 6 lines and points. Can you make one?

Not any arbitrary number of points and lines can satisfy these properties. The next possible finite projective plane is known to have 13 points and 13 lines. (Yes! always the number of points and lines turn out to be same for a finite projective plane).

Extras! For mathematically inclined readers Click to expand

It is known that the number of lines and points is always equal for a finite projective plane (let this number be $N$). Furthermore, all lines contain the same number of points, and all points have the same number of lines incident on them. And these two numbers are equal as well! Say this number, the number of points on a line (as well as the number of lines coming from a point), is $k$. We can write $N = k^2 - k + 1$, and it is conjectured that $k-1$ has to be prime. $k$ is called the order of the projective plane.

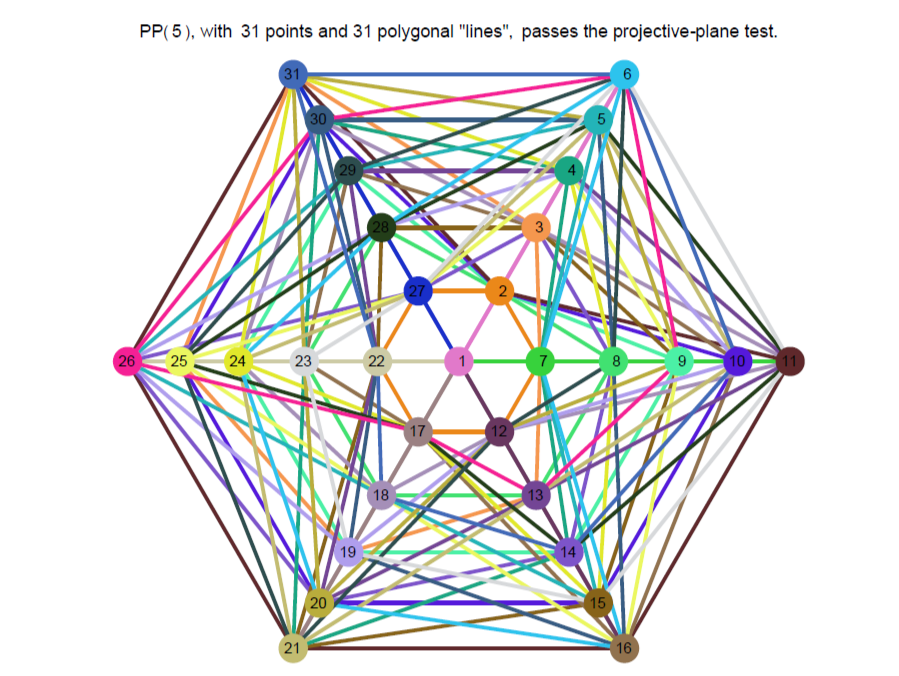

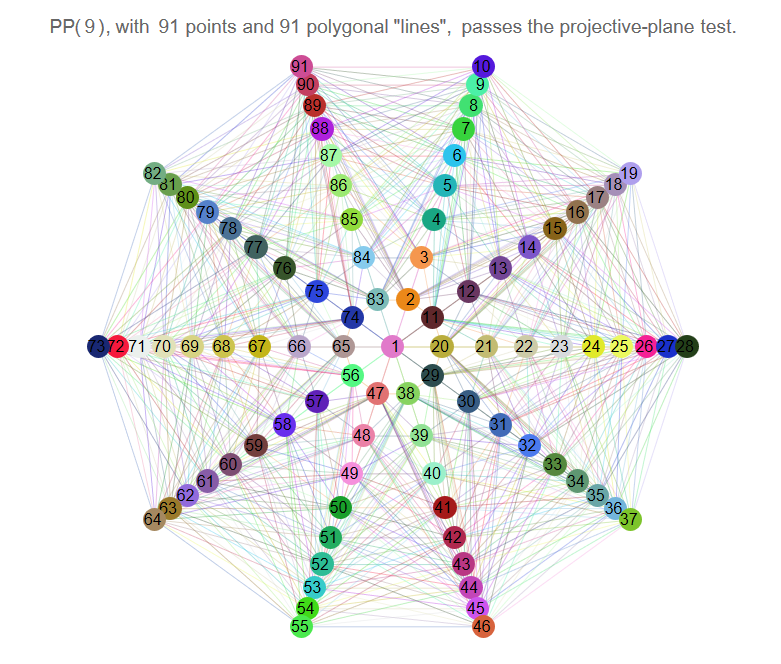

Larger projective planes become more challenging to draw. They are complex but pretty looking. You can try to pull the one with 13 lines and 13 points as a challenge.

This is a finite projective plane with 31 lines and points.

This with 91!

Now, finally, let us come back to our puzzle. What if I say the Fano plane is the solution to our puzzle? Yes! We can consider the line to be the days of the week and points to be the courses (or vice versa), and you will see all the needed conditions are satisfied!

References and sources

Finite Projective Planes and Quadratic Forms with Applications, Xinkai Wu

The above two examples of projective planes with 31 and 91 lines and points is taken from WOLFRAM Demonstrations Project, Projective Planes of Low Order. They have really cool animations. You can check out and play with it by selecting pairs of lines and seeing if they exactly intersect at a line and vice versa.