RSA Cryptography

Have you wondered how security is ensured in communication channels? When we use Instagram or chat with a friend in WhatsApp, it says end-to-end encrypted. How is this achieved? This blog post gives an introduction to one of the most widely used cryptographic systems, the RSA.

Prerequisite: The blog post assumes the readers to be familiar with basic group theory.

Introduction

To understand how secure communication is achieved in real life, let us consider a toy model. Imagine that you and your friend, who will soon leave abroad, meet one day and decide that from now on, you will write and communicate through letters. But as you are working on a secret mission, you do not want any eavesdropper who catches hold of your letter to know the message. What will you do?

One simple cipher technique is to communicate and have a shared secret key. Suppose, in this toy example, you and your friend decide to shift every letter appearing in the message by 5 places; then, the secret key is 5. Only if the sender and receiver know this can they encrypt and decrypt the message. This form of protocol for encryption and decryption is called private key cryptography.

However, in today’s world, we can communicate securely and at ease with strangers we have never met. Without meeting, how can one communicate the secret key? Also, notice that one can not send the secret key through a public channel as any eavesdropper can then very easily decipher their message. The ingeniousness behind security without exchange of private key is the invention of public key cryptography by Whitfield Diffie, Martin Hellman, and Ralph Merkle in 1976.

RSA is one of the most widely used public key cryptography. The idea behind RSA is as follows:

Suppose you and your friend want to communicate. This time, both of you have two keys each, one a public key, that is publicly available to everyone and a private key that no one other than the owner knows. Note that these keys are not common to both you and your friend, so this does not require you to meet to share the secret physically. One possible scheme to communicate securely is as follows:

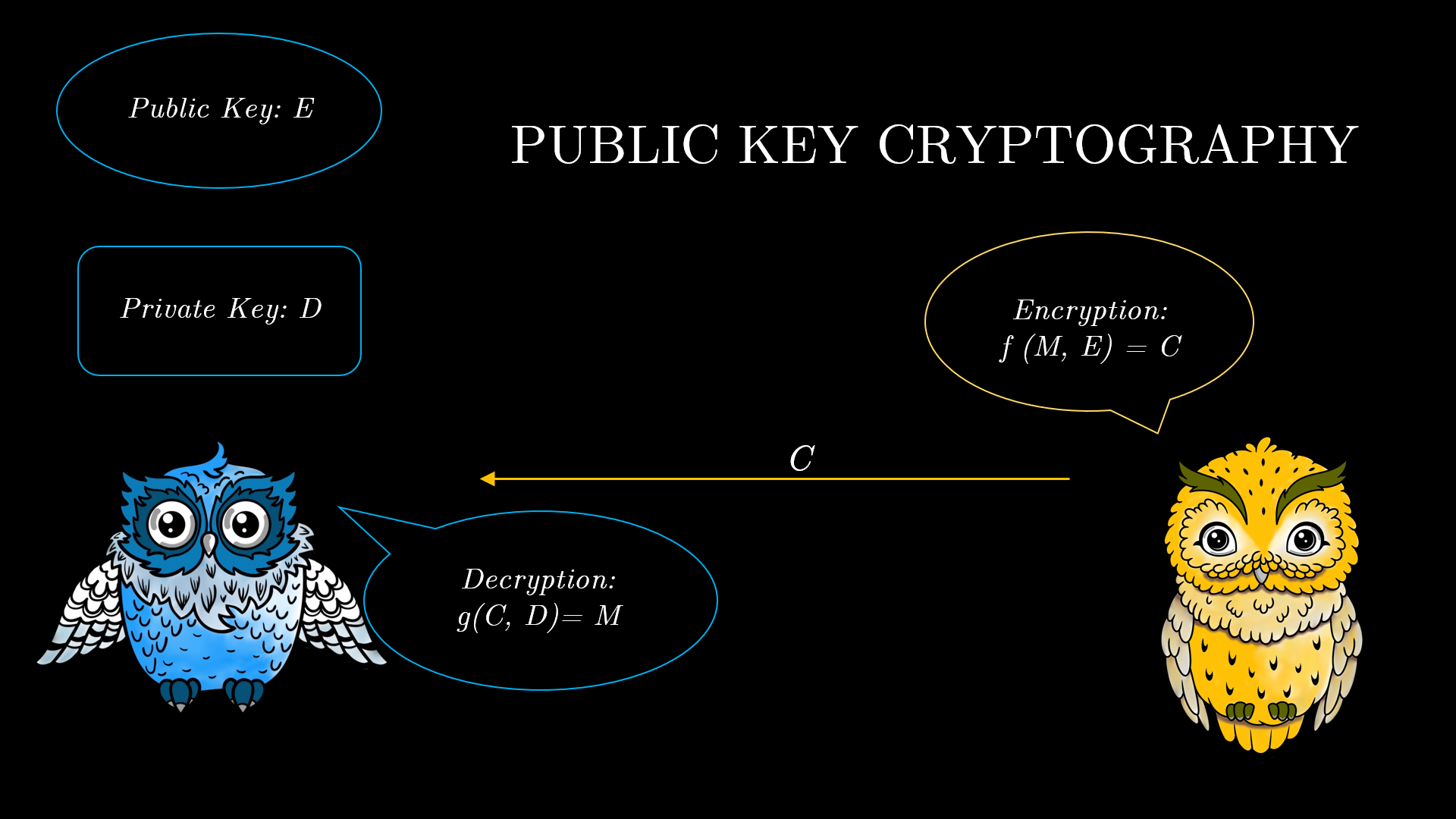

Your friend encrypts their message through the function $f$, invoking the public key $E$, and sends the encrypted message $C$ to you. You then use the function $g$ to decrypt the message with the help of your private key $D$. The functions $f$ and $g$ are released publicly as a part of the protocol. Public key cryptography works on the basis that the function $f$ is extremely difficult to invert; that is, getting the message $M$ from the cipher text $C$ is extremely hard. But this becomes easy with $D$, the private key. Thus, such protocols heavily rely on the computational hardness of a problem.

Basically, you need to pick the functions such that though the entire communication happens via a public channel, no eavesdropper should be able to invert the function to get the message from the cipher. Inverting the function should be a really hard task. At the same time, the genuine receiver should be able to invert it with ease; this should be aided by the receiver’s private key.

Now, let us understand this better by looking into the workings of RSA. RSA’s security relies on the hardness of the discrete logarithm problem, which we will see shortly.

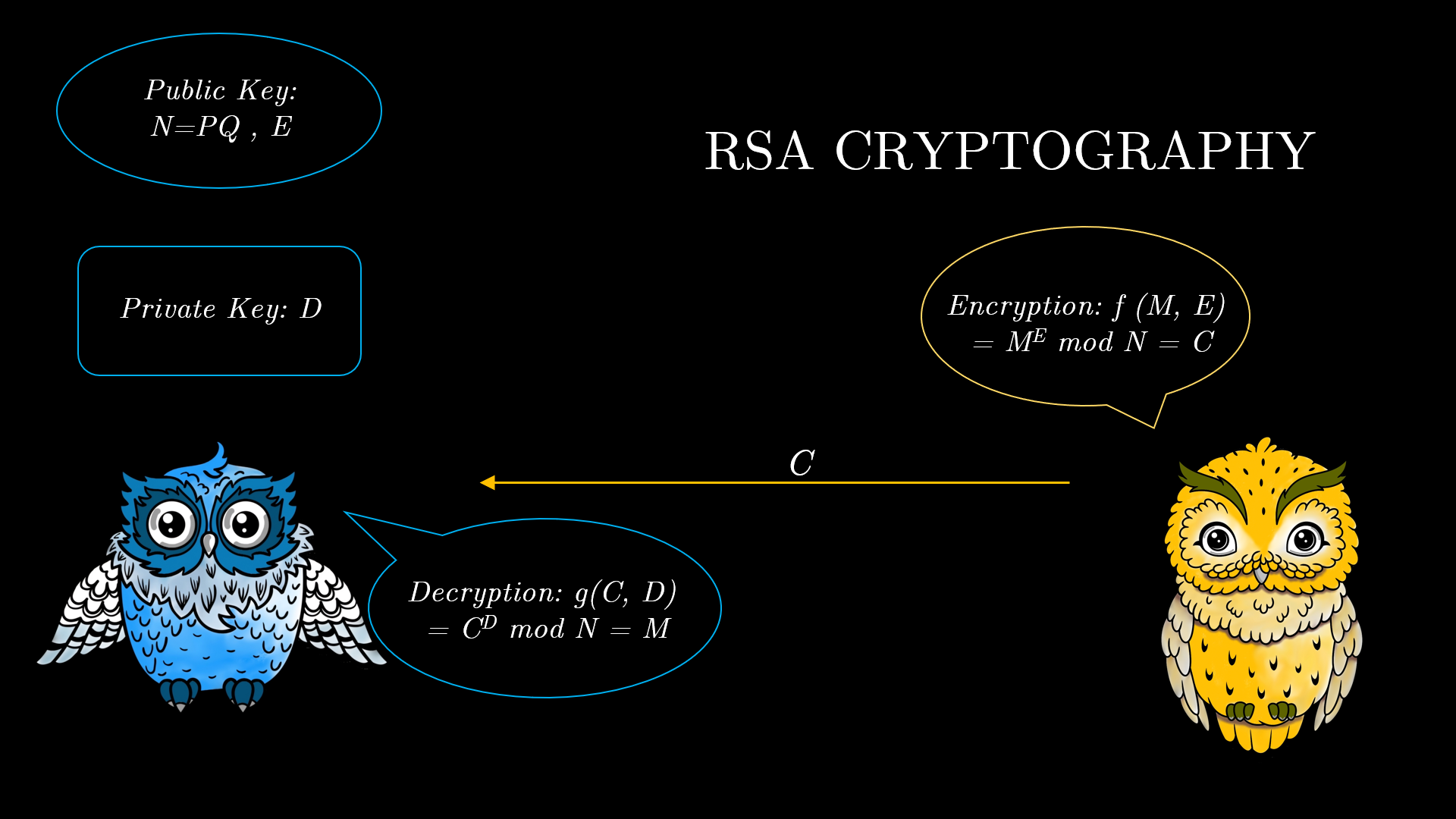

The setup for the RSA scheme is as follows:

The public and private keys are indicated in the diagram. The functions $g$ and $f$ are $f(M,E)=M^E \mod N =C$ and $f(C,D)= C^D \mod N =M$. The reverse operation to this exponentiation modulo $N$ is called finding the discrete log of C to the base E modulo N, and this is an extremely hard problem computationally. Also, the private and public keys in the RSA are not chosen randomly. They are cleverly chosen to harness the hardness of the discrete log problem.

The keys for the RSA algorithm are generated in the following way:

• Choose $P$ and $Q$ very large primes. Compute $N = P Q$.

• $N$ is released as a part of the public key. $N$ will be used as the modulo arithmetic for both public and private keys. Its length, usually expressed in bits, is the key length.

• Let $R = (P − 1)(Q − 1)$ the totient function.

• Choose integer $E$ such that $1 < E < R$ and $E$ is coprime with $R$.

• Determine $D$ such that $ED \mod R = 1$, that is $D = E−1 \mod R$, the modular multiplicative inverse of $E \mod R$. $D$ is the private key.

You may wonder why we have such a complicated strategy to choose the public and private keys. The reason lies in the underlying number theoretical results, without which RSA wouldn’t be possible.

Let us take a small detour into the interesting world of number theory to understand the RSA key generation protocol.

Number Theoretical Foundations

Finite Groups Modulo $N$

Let $(\mathbb{Z} / n \mathbb{Z})^\times$ denote the multiplicative group of integers modulo $N$ that are coprime to $N$. Formally $(\mathbb{Z} / n \mathbb{Z})^\times = { a \in \mathbb{Z} \mid 1 \leq a < N \text{ and } \gcd(a, N) = 1 }$.

If $n$ is not a prime, it has all elements of $(\mathbb{Z} / n \mathbb{Z})$ which are coprime with $n$. If $n$ is prime, $(\mathbb{Z} / n \mathbb{Z})^\times$ is the same as $(\mathbb{Z} / n \mathbb{Z})$. This set forms a group under multiplication modulo $N$, with order $\varphi(N)$, where $\varphi$ is Euler’s totient function. This denotes the cardinality of numbers, which are coprime to $N$.

Example: For $N = 15$, $(\mathbb{Z} / 15 \mathbb{Z})^\times = {1, 2, 4, 7, 8, 11, 13, 14}$ and $\varphi(15) = 8$.

Note that the Euler totient function is a multiplicative function, that is, if two numbers $m$ and $n$ are relatively prime, that $\varphi(mn) = \varphi(m) \varphi(n)$.

Example: For $N=3$, $(\mathbb{Z} / 3 \mathbb{Z})^\times = {1,2}$ and for $(\mathbb{Z} / 5 \mathbb{Z})^\times = {1,2,3,4}$. Note that $\varphi(3) \times \varphi(5) = \varphi(15) = 8$.

Order of an Element

Definition: The order of an element $a \in (\mathbb{Z} / n \mathbb{Z})^\times$ is the smallest positive integer $r$ such that: $a^r \equiv 1 \mod{N}$.

By Lagrange’s theorem, we emphasize that the order of the cyclic group generated by an element $a$ given by ${1,a,a^2,\dots,a^{r-1}}$ such that $a^r=1\mod N$, divides the order of the group, hence $r$ divides $\varphi(N)$.

Fermat-Euler Theorem

Theorem (Fermat’s Little Theorem): For any $a \in \mathbb{Z}$, $p$ some prime, \(a^{p} \equiv a \mod{p}.\)

Theorem(Fermat-Euler): For any $a \in (\mathbb{Z} / n \mathbb{Z})^\times$, \(a^{\varphi(N)} \equiv 1 \mod{N}.\)

Euler’s theorem is a generalization of Fermat’s little theorem (For any prime $\varphi(p)=p-1$ since there exist $p-1$ numbers co-prime to $p$ smaller than $p$, hence $a^{\varphi(p)}\mod p\equiv a^{p+1}\mod p\equiv 1\mod p$, thereby $a^p\equiv a\mod p$), which can be understood from group theoretical principles. Since the order of any element in $(\mathbb{Z} / n \mathbb{Z})^\times$ divides the order of $(\mathbb{Z} / n \mathbb{Z})^\times$, we have $a^r\equiv 1\mod N$ where $r$ divides $\varphi(N)$. Thereby we have $\varphi(N)=rk$ for some $k$, then $a^{\varphi(N)}\mod N\equiv (a^r)^k\mod N=1\mod N$.

Coming back to RSA

Now, let’s revisit the key generation aided with a number-theoretical lens. Recall that $R$ was defined as $R=(P-1)(Q-1)$ the totient function. Note that as $\varphi(N) = \varphi(P) \times \varphi(Q)=(P-1)(Q-1)$ since $\varphi(P)$ and $\varphi(Q)$ are $P-1$ and $Q-1$ respectively. As $P$ and $Q$ are primes, their all $P-1$ and $Q-1$ natural numbers before $P$ and $Q$ are co-prime to $P$ and $Q$, respectively. And we choose an integer $E$ as a public key, such that $1< E < R$ and $E$ is coprime with $R$. This means $E \in \varphi(R)$.

The decryption works as $D$ is chosen such that

$ED \mod R =1 \implies ED= 1 + xR$ where $x \in \mathbb{Z}$.

Hence, we have,

\[C^D \ {\rm mod} \ N = (M^E)^D \ {\rm mod} \ N\]\(= M^{ED} \ {\rm mod} \ N = (M \ {\rm mod} \ N)(M^{xR} \ {\rm mod} \ N) = M \ {\rm mod} \ N\)

The last line follows from the fact that $M^R \mod N = 1$ as $R$ is totient of $N$.

A malicious Eve can eavesdrop on Alice and Bob’s conversation and get $C$. But what guarantees that she cannot get $M$ from $C$ given the protocol $N$ and $E$?

Classical computers can efficiently compute $D$ such that $ED \mod R = 1$, provided $R$ is known. So, the real difficulty lies in computing $R$ from $E, N$, and $C$, that is, finding the prime factors of $N$. So, the security of RSA lies in the fact that factoring is a computationally very hard problem. This is no longer true in the case of a quantum computer. In the upcoming blog post, we will delve into the quantum computing algorithm- Shor’s algorithm- that can break RSA.

Reference

Quantum Information and Quantum Computing. Lectures. Sreejith G. J.