Knowing When to Stop Looking for Better Ways to Solve Your Problems

Given any problem, is it always possible to develop better or faster methods to solve it? Is there such a thing as the best method for solving a problem? If so, how can one determine which method is the best? And finally, when should one decide to stop searching for an even better or faster way to get to the solution?

The previous blog post offered an intuition into such questions through games. This post will delve into the mathematics.

The keen readers who read the previous blog post might have noticed that what one is essentially trying to do while playing these games is to search in a sorted list of numbers. We ended the blog post with a suggestion that possibly the best strategy is to divide the space of possible numbers into two equal halves every time. We named this strategy divide half.

I promised to prove to you that, no matter how clever one is, one can not do better than the divide half strategy.

To recall, the game we considered in the previous blog post) was as follows: The computer picked a number (between 1 and 10,000), and you could ask it questions of the following and try to guess the number:

- Is the number greater than x?

- Is the number lesser than x?

- Is the number equal to x? Your task is to guess the number with the least number of questions.

All the possible strategies to play the above game come under what is called comparison-based algorithms.

The divide half strategy is: to ask questions that rule out half the possible numbers at every step. Now, let us compute how many steps this strategy takes to get to the number.

At every step, you are ruling out half the numbers from the previous step. So, if we start with $n$ numbers (in our case, $n =10000$), at the end of step 1, we have $\frac{n}{2}$. After step 2 we have $\frac{(\frac{n}{2})}{2}$, that is $\frac{n}{2^2}$. At the end of the 3rd step, $\frac{n}{2^3}$, and so on. When do we stop? Say we stop after $s$ many steps. We stop when from 100 numbers, we get to exactly 1 number. So, we want our $\frac{n}{2^s} = 1$.

How many steps does this take?

#steps = ?

$\frac{n}{2^{(\text{# steps)}}} = 1$

$\implies 2^{(\text{# steps})} = n$

$\implies$ # steps $= \log_2 n$

Thus, our divide half takes $\log_2 n$ many steps.

What is the guarantee that no matter how clever one is, one cannot come up with another strategy to find a number from a sorted list in less than $\log_2 n$ steps?

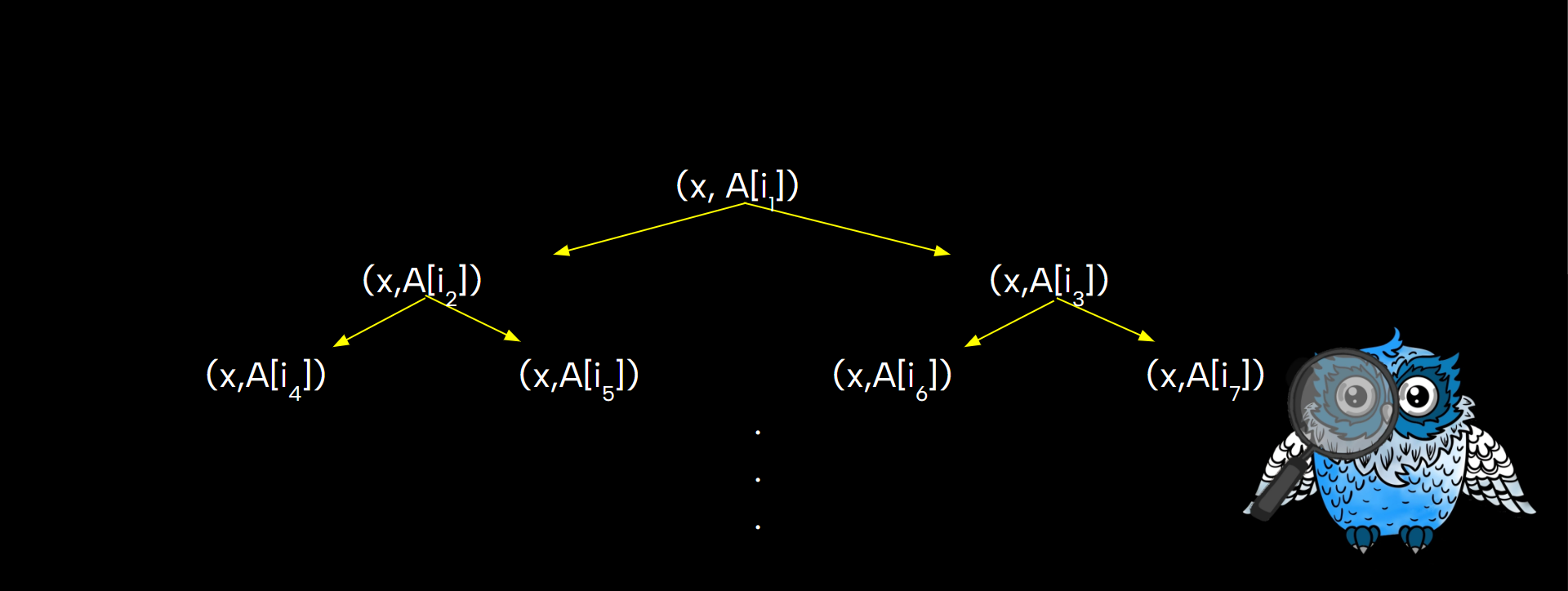

Let us consider a generic setup, where we do not consider any particular strategy to play our number-guessing game. According to the rules of the game, to find the number, we can essentially ask whether the number, say $x$, is greater than, or lesser than, some number, say $a_1$. Asking whether it is equal to some number at the very start is not going to be efficient.

Depending on whether $x > a_1$ or not, the number $x$ can lie on either side of $a_1$ on the number line. And according to the answer to the question “Is $x > a_1$?” one will ask the subsequent question, and so on.

What are the exact values of these $a_i$s and whether we divide the possible numbers equally or not? All these depend on the specific strategy we adopt.

When will this tree end? Will we keep drawing the nodes forever?

We stop when we exhaust all possible questions and find the value we are searching for. Eventually, we will converge to nodes of the form $x = b_1$, $x = b_2$ $\dots$, and $x = b_n$ if the numbers considered are between 1 and $n$.

Tree? (Click to expand)

The structure we drew (given in the above picture) is a graph theoretical object called a tree. We call these nodes as vertices and these lines as edges. The last nodes, those that do not have descendants, are called leaves.

The single node from which the tree starts is called the root node. In this example, at every step, we divide the space into two (based on whether $x$ is less than or greater than the number). Such trees that have a root node and have at most two branches from every node are called rooted binary trees.

If the strategy is such that every question does not equally divide the space of possible numbers, then intuitively, one would have to ask more questions on one side of the tree than the other. The tree corresponding to such strategies is called an unbalanced rooted binary tree.

Whereas our divide half strategy gives a balanced rooted binary tree as it divides the space of possible numbers equally after every question.

Notice that, in this context, the height of the tree captures the number of questions one should ask to find the number. So, if we could prove that divide half has the least height among all such trees one can draw, then we have proven that divide half is the best strategy.

The following Python code lets you see this pictorially. It shows that a balanced-rooted binary tree has the least height compared to any other unbalanced-rooted binary tree. The code lets you choose the number of leaves (in this context, the number $n$, i.e. search space size), and it shows both a balanced and unbalanced binary tree with their corresponding heights. It generates randomly the unbalanced tree every time.

Click to Compare the Heights of Trees.

If you had meddled with the above interactive code, you would notice that the height of a balanced rooted binary tree is nothing but equal to $\log_2 n$ and is always less than the height of any unbalanced rooted binary tree. Eureka! It matches the number of steps taken by our divide half strategy.

So in these two blog post we considered the problem of searching in a sorted list. We kept asking the question, is this the best method to solve the problem and tried to improve our strategy to solve it. This art of looking for better methods to solve a given problem is called algorithmic thinking.

We realized that we could not improve further from our divide half strategy, and we proved this. Thus we have a concrete lower bound to this problem.

The first method we saw, where we drew out the tree and used it to compute our $\log_2 n$, is called the decision tree method. The second one, where we used a cunning guess block to devise a better strategy, is called the adversary method (Refer the post Games!). These methods are not specific to the searching in sorted list problem. These can be used to give lower bounds to many similar problems. One example is for the sorting problem. As an exercise try to give a lower bound for the sorting problem.

Sorting Problem (Click to see the problem statement)

Given a list of n distinct elements how many steps do you need to sort the list of elements? At every step you get to compare two elements and sort. What is the least number of steps needed to do this? And give the best strategy to do this.

Hint (Click to expand)

Think about the number of leaves here. It will be $n!$($n$ factorial). Why?

There is yet another powerful method used to give lower bounds to problems – called the method of reductions. Hopefully, in one of the later blog posts, I will present this powerful method as well.

Reference:

Lecture on Lower Bounds by Prof. Venkatesh Raman, IMSc

Extras:

This winter, I had the honor of returning to my high school as a guest speaker for a workshop. The talk was an outcome of this blog post where I also tried to provided a overall glimpse into the world of theoretical computer science. As a small way to extend the learning, I’m happy to share the slides and worksheet I prepared for the workshop, hoping they will be helpful for anyone interested in these ideas.